Diagnostics in Motion: Reimagining Equity, Technology, and the Role of the Medical Laboratory Technologist

Introduction: The Problem We Must Name

As a Medical Laboratory Technologist (MLT) in Ontario, I am always conscious that every sample I touch is a life, a story, a person waiting for answers. This course has made me understand a difficult truth: Canada has entrenched and longstanding inequities in access to diagnostic testing, which determine who is tested early, who is diagnosed late, and whose results are used to inform clinical decisions.

The scale of this problem is significant, and Indigenous peoples in Canada have reduced access to primary care, and more than one in four Indigenous peoples report unmet healthcare needs compared with 16% of non-Indigenous Canadians (Barbo & Alam, 2024). Furthermore, race-based data gaps only add to the complexity, essentially rendering entire communities invisible in national health surveillance (Jamieson et al., 2025). As a consequence, these structural gaps dictate the diagnostic pathway from the very beginning, who is able to enter the system, who gets timely testing, and who is left waiting on the margins.

To examine this problem, I applied the Social-Ecological Model (SEM), which includes structural, community, interpersonal, individual and technological levels. Each level plays a role in determining who receives diagnostic testing and how the system responds. Using this framework, I arrived at one conclusion: equity and technology need to be developed concurrently, or else Canada’s diagnostic system will never achieve true health equity. Therefore, I believe this conclusion is crucial for the future of Canada’s diagnostic system.

Level 1: Structural & System-Level Determinants

These structural forces are not theoretical; they are policies, funding arrangements, data standards, and institutional practices that determine who gains access to the diagnostic system. Jamieson et al. (2025) demonstrate that race-based health data in Canada is collected inconsistently, meaning that key populations are invisible in the evidence that guides diagnostic policy. This invisibility creates inequity long before any specimen is collected.

At the same time, genomic cancer testing provides a stark example of such structural disparities. This is due to the fact that jurisdictional oversight and assessment of genomic medicine remain a piecemeal activity across provinces, resulting in unequal access to advanced diagnostics (Husereau et al., 2023). In some jurisdictions, precision diagnostic tools are rapidly adopted; however, elsewhere, patients experience years of delay, and these disparities originate upstream, long before the sample is processed in the laboratory. This demonstrates how fragmentation determines who receives timely testing, and who does not. Consequently, a fair diagnostic system will thus depend on the establishment of a coordinated, inclusive and highly regulated infrastructure that allows equal access to all territories.

Level 2: Community & Health System Access

Diagnostic inequities also start in communities. Access to primary care, distance to travel, availability of services and whether care is culturally safe are all determinants of whether someone even enters the diagnostic stream. Barbo and Alam (2024) show that discrimination and culturally unsafe care have caused deep distrust among Indigenous patients, who often delay care until their disease is advanced.

However, community-led models offer some solutions. The Kidney Check program, co-created with Indigenous communities, has brought point-of-care testing to rural and remote areas, allowing for earlier detection while also rebuilding trust, as Curtis et al. noted in 2021. The Kidney Check program shows that when care models are designed and led by communities, traditional barriers can be reduced. Therefore, access is not just about geography, but also about respect, safety, and partnership with local populations.

Level 3: Interpersonal & Clinical Encounter Level

People are more likely to engage in and complete diagnostic testing when they are treated with dignity, believed, and made to feel culturally safe. Barbo and Alam (2024) remind us that mistrust among Indigenous peoples is the result of lived discrimination in the health-care system. In turn, it influences whether patients agree to tests, accept referrals and return for follow-up appointments because when patients feel valued and respected, they are much more likely to engage in the health care system and adhere to recommended care.

At this level, clinicians play a pivotal role, because the way tests are explained, concerns are legitimized, and cultural safety is demonstrated directly impacts a patient’s diagnostic journey. Even when services are available, a rushed visit, a dismissive tone, or unexamined bias can halt the process. Therefore, equitable diagnostics require interpersonal care that is relational, compassionate, and culturally informed.

Level 4: Individual-Level Factors

Individual-level factors impact the movement of an individual through the diagnostic care process. Health literacy, education, income, digital literacy, experiences with the health care system and personal beliefs influence whether an individual undergoes testing and whether they complete testing. Canada Health Infoway (2023) suggests that people with limited digital skills or those with unstable internet connectivity are less likely to participate in virtual diagnostic procedures, which exemplifies how the digital divide leads to missed or delayed care.

Additionally, individuals who have experienced trauma or negative experiences with the health system in the past are more likely to delay seeking care or avoid it altogether. These individual barriers seldom occur alone; instead, they intersect with community conditions and structural determinants to further exacerbate inequities in access to timely and accurate diagnosis.

Level 5: Technology & Innovation Layer

Technology influences every stage of the diagnostic pathway. AI can accelerate interpretation, flag abnormalities, and support clinical decision-making, but datasets lacking diversity risk reinforcing inequities. Genomic medicine allows for precise diagnosis, yet its availability remains concentrated in specialized urban centres, limiting access for rural and remote populations.

Digital tools such as virtual care and integrated data platforms can improve communication and continuity of care, but they can also exclude people who lack devices, internet access, or digital literacy. Policy Horizons Canada (2025) cautions that without strong ethical foundations and equity-centered design, the emerging technologies may actually exacerbate rather than reduce existing inequities. Therefore, in order to prevent this, technology should be developed and deployed with intention and equity should be prioritized at all levels.

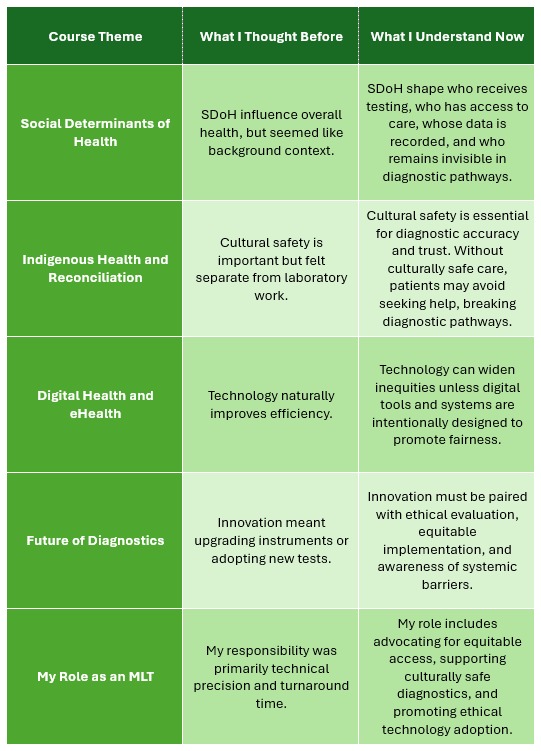

Table 1: Evolution of Learning Across Key Course Themes

Explanation:

As my work began, the frame was narrow and technical, but over time, the frame expanded to a systemic, equity-centered approach. Laboratory practice was no longer a separate entity, because it was now a node in a web of social determinants and power structures. Reconciliation was a methodological and ethical imperative, and therefore, technology moved from being a tool to a transformation agent. Consequently, each thread connected to create an integrated lens that examines practice, policy, and justice within the same frame of reference.

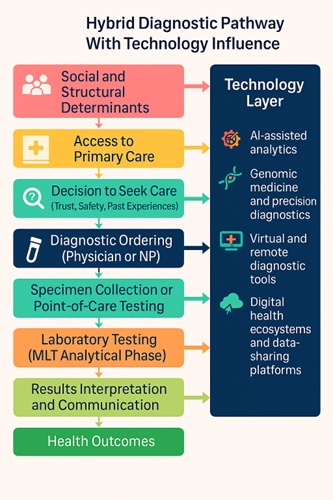

Figure 1: Hybrid Diagnostic Pathway With Technology Influence

Explanation:

The figure shows how inequalities are nested within each step of the diagnostic pathway, before the first clinical encounter and far beyond the laboratory, and the social and structural determinants shape entry, passage through care and consequences. Technology is a thread that runs throughout, influencing access, quality and outcomes, because together, these determinants co-produce disparities and opportunities for redress along the whole pathway.

Conclusion: Bringing the Levels Together

Throughout the course I was actively engaged in the course and engaged in the peer discussions and presentations, although I did not receive direct feedback on my own work, the dialogue and feedback from peers encouraged me to think critically about my own work. I was able to see my peers making connections between equity, reconciliation and digital transformation and diagnostic practice, and that helped me to better understand the Canadian health care system. The peer dialogue also served to reinforce a key point for me: that equity in diagnostics is not an academic pursuit, but rather a shared professional responsibility.

Working through this multilevel model reshaped how I understand diagnostics and my role as an MLT. Structural inequities determine who enters diagnostic systems. Community factors shape trust and access. Interpersonal interactions influence whether patients feel safe seeking care. Individual experiences determine engagement. Technology can bridge or widen these gaps depending on how it is implemented.

A strong diagnostic system cannot be judged only by the sophistication of its tools; it must also be evaluated by its fairness, accessibility, and commitment to cultural safety. This course helped me see that my role extends beyond producing accurate results, it includes advocating for equity, supporting culturally safe practices, and promoting ethical technology adoption.

I want to help build a diagnostic future where innovation and justice move forward together, ensuring that every sample and every person is treated with dignity, fairness, and meaningful access to care.

References:

Barbo, G., & Alam, S. (2024). Indigenous people’s experiences of primary health care in Canada: A qualitative systematic review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 44(4), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.44.4.01

Canada Health Infoway. (2023). Canadian digital health survey 2023: Virtual care and digital health uptake. https://insights.infoway-inforoute.ca/2023-digital-health-survey

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2024). Annual report 2023–2024. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/cihi-annual-report-2023-2024-en.pdf

Curtis, S., et al. (2021). Kidney Check point-of-care testing, furthering patient engagement and patient-centered care in Canada’s rural and remote Indigenous communities: Program report. CanSOLVE CKD. https://cansolveckd.ca/publications/kidney-check-point-of-care-testing-furthering-patient-engagement-and-patient-centered-care-in-canadas-rural-and-remote-indigenous-communities-program-report/

Husereau, D., Bombard, Y., Stockley, T., Carter, M., Davey, S., Lemaire, D., Nohr, E., Park, P., Spatz, A., Williams, C., & Feilotter, H. (2023). Future role of health-technology assessment for genomic medicine in oncology: A Canadian laboratory perspective. Current Oncology, 30(11), 9660–9669. https://doi.org/10.3390/curroncol30110700

Jamieson, M., Blair, A., Jackson, B., & Siddiqi, A. (2025). Race-based sampling, measurement and monitoring in health data: Promising practices to address racial health inequities and their determinants in Black Canadians. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 45(4), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.45.4.02

Policy Horizons Canada. (2025). Foresight on artificial intelligence: Implications for health systems policy and governance. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2025/hpc-phc/PH4-210-2025-eng.pdf