From Bench to Policy: What Type 2 Diabetes Teaches Us About Multilevel Health

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is increasing at an alarming rate in Canada with over 3.6 million people affected, because it has a disproportionate burden on older, low-income and Indigenous Ontarians (Diabetes Canada, 2024). As a medical laboratory technologist (MLT), I have observed that the results of diagnostics are reflective of and perpetuate the broader inequities that exist within society, because each result of hemoglobin A1C or fasting glucose is not just a numerical value, but is reflective of the behavioural choices, social circumstances, and systemic forces that shape that value. To elucidate these inter-relationships further, this analysis employs the Social Ecological Model (SEM) to explore T2D through a multi-level public health perspective, grounded in laboratory practice in Ontario.

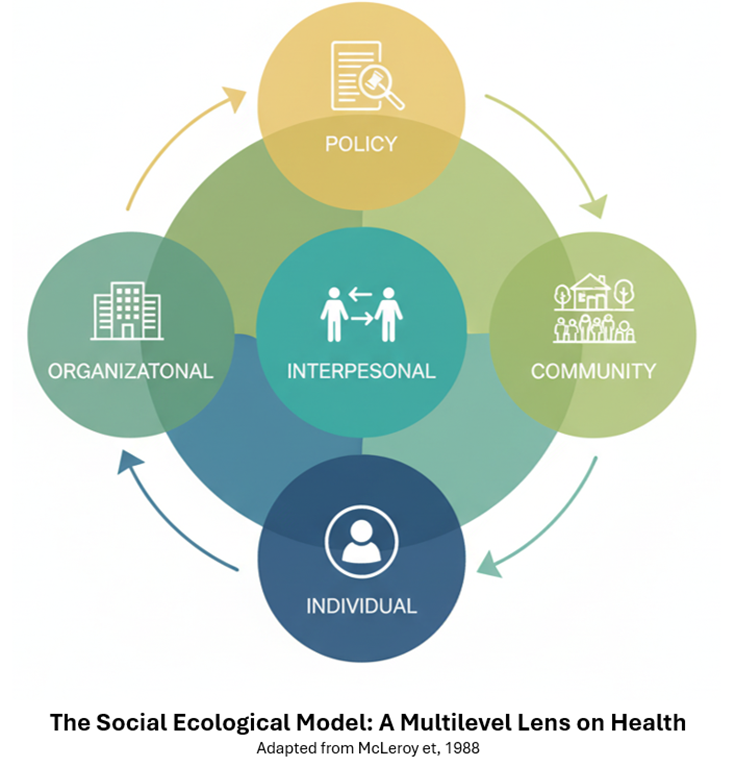

The Social Ecological Model: A Multilevel Lens on Health

This paper builds on earlier work exploring multilevel determinants of T2D and Ontario laboratory professionals by using the SEM and more recent data. The SEM posits that health is the outcome of multiple, interacting levels: individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy (McLeroy et al., 1988), and drawing on Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977), it presumes that individuals are situated within nested, interacting systems. In public health, the SEM looks beyond individual responsibility to consider the social, structural, and political factors that influence health outcomes (McLeroy et al., 1988), because multilevel approaches offer a framework to understand how health inequities are created where social identity, policy, and place intersect (Evans et al., 2018). The SEM is consistent with current conceptions of health that value adaptability and social context over standard norms (Huber et al., 2011), and in the context of laboratory medicine, this means that laboratory test results are not discrete entities, but are instead a function of the systemic determinants of health, including access to care, education, and socioeconomic status (PHAC, 2023).

Figure 1: The Social Ecological Model framework illustrating five levels of influence on health outcomes.

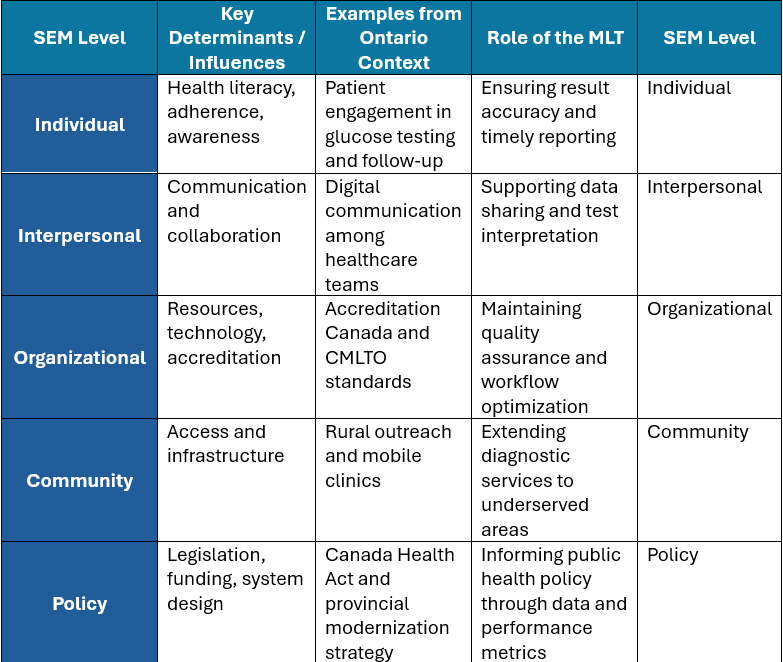

Applying the SEM to Type 2 Diabetes in Ontario Laboratory Practice

- Individual Level

At the individual level, regular testing plays a key role in disease control, and testing rates are higher among people with higher income levels in Ontario (PHAC, 2023). Many in marginalized communities delay testing due to costs, transportation barriers, and limited knowledge, exacerbating disparities in disease control (PHAC, 2023). Laboratory technologists play an important role in the individual’s care, as they provide the care team with accurate and timely results, and because delays or inaccuracies of even a few minutes can change the treatment plan. Accurate diagnostics enable more rapid adjustment, build trust in care, and ultimately strengthen the patient’s sense of control and ability to self-manage.

- Interpersonal Level

Effective collaboration and communication among healthcare professionals is essential in order to provide high quality patient care and achieve the best possible outcomes for patients. Effective exchange between MLTs, physicians, nurses, and diabetes educators ensures appropriate test utilization and interpretation. During the COVID-19 pandemic, digital tools such as encrypted messaging improved interprofessional efficiency and patient safety (De Benedictis et al., 2019). These communication networks demonstrate that laboratory data gain meaning through human collaboration, linking diagnostics with compassionate care.

- Organizational Level

Organizational factors including staffing ratios, automation, continuing education, and accreditation all contribute to the quality of laboratory practice (Accreditation Canada, 2023; CMLTO, 2024), although laboratories that are accredited and regulated are held to high standards, and there is a variation in technology and staffing across regions which affects the care provided. Sustainable organizational systems are inextricably linked to family and community health and therefore emphasize the need for fair infrastructure in Ontario laboratories (Browne et al., 2024), because sustainable systems require that medical laboratory technologists deliver evidence-based diagnostic information that protects patients and informs decision making across the continuum of care (CSMLS, 2023).

- Community Level

Community context determines access to testing and chronic disease management, and in rural and Northern Ontario, where long travel distances and fewer laboratory testing sites exist, there are inequities in screening and follow up (Ontario Health, 2024). The initiative also includes community-based programs and mobile testing units (Ontario, 2024), and in these programs, MLTs can interact with public health, essentially bringing the lab to public health, making diagnostics more available to the public and resulting in earlier detection of complications.

- Policy Level

Ontario’s diagnostic systems function within a publicly funded system in accordance with the Canada Health Act (1985), which emphasizes access and universality, however, disparities persist that are influenced by social determinants of health such as income, place, and education (PHAC, 2023; Evans et al., 2018). The Ontario Ministry of Health’s 2023–24 Published Plan and Annual Report outlines ongoing modernization efforts to enhance efficiency, integrate data systems, and raise province-wide quality standards (Ontario Ministry of Health, 2023), and this policy direction is the outermost layer of the SEM, where institutional and legislative changes impact all other levels. For instance, The Ministry’s Laboratory Modernization Strategy affects institutional workflows, community access, and individual compliance through faster turnaround and digital reporting, and MLTs also have an indirect but critical role in public health policy and performance measurement by generating the data behind health indicators that inform evidence-based decision making and accountability across the system.

Table 1: Application of the Social Ecological Model to Type 2 Diabetes in Ontario’s Laboratory Practice

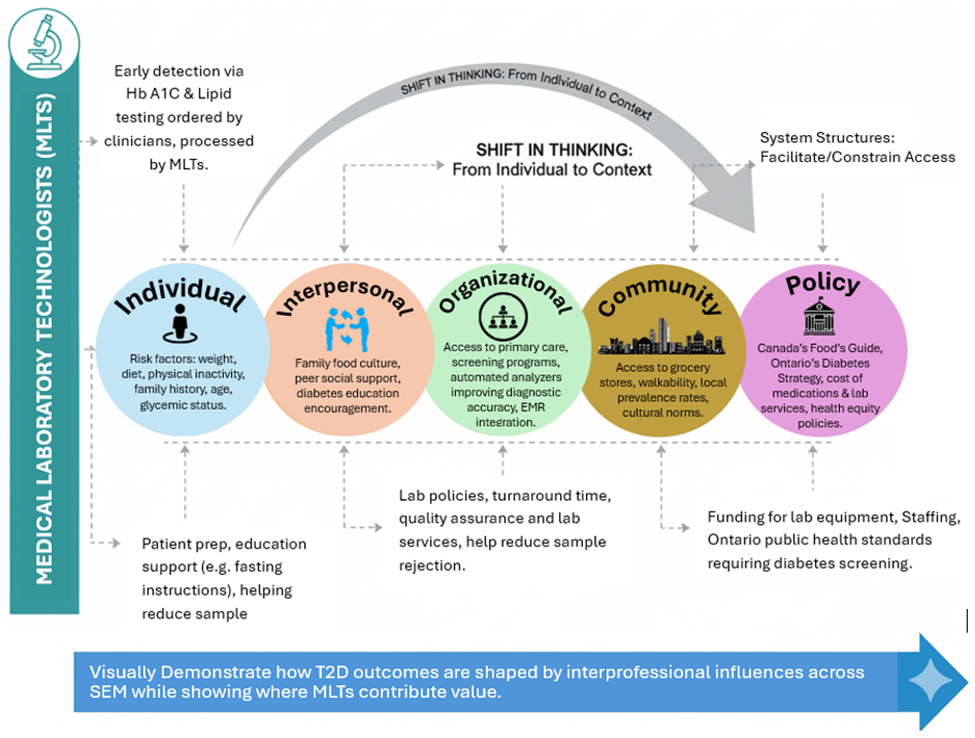

Integrating Foundational Learning

This course changed the way I think about T2D because it showed me how my professional identity and interprofessional practice relate to the information I generate as an MLT. It helped me understand how my role contributes to team-based decision making through timely and accurate diagnostic testing, and it taught me about the evolving definitions of health, policy, and equity, and how system structures facilitate or constrain access to screening, education, and ongoing care for diabetes. By looking at all these levels at the same time, the course helped me shift my thinking from individual behaviour to the context in which people live, work and make choices, therefore I now interpret T2D as a problem that spans individual knowledge and motivation, interpersonal support from family and care teams, organizational practices, community factors, and policy levers that determine coverage, quality standards, and data reporting through the SEM. Consequently, I will apply this integrated approach to guide practical, justice-oriented solutions to the problem of T2D, such as earlier detection through equitable screening pathways, coordinated follow-up based on lab results, and policies that reduce barriers for marginalized groups, and thus the course helped me move toward a multilevel, equity-focused approach to prevention and care.

Incorporating Peer Feedback

By reviewing my classmates’ posts, I learned about the application of multilevel frameworks in various professions, and looking at the manner in which nurses, respiratory therapists, and program directors presented their topics helped me to see the common need for interprofessional collaboration and context. The indirect form of peer learning helped me to better apply theoretical knowledge into practice in interprofessional settings without any formal feedback, by viewing a variety of applications and aligning them with common goals.

Figure 2: Infographic, “From Bench to Community: Multilevel Determinants of Type 2 Diabetes Outcomes”

Conclusion:

Type 2 diabetes through the lens of the Social Ecological demonstrates that health care decisions and outcomes are inextricably linked across individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy levels, and for Ontario’s Medical Laboratory Technologists, this means a dual commitment to unerring diagnostic accuracy and to the pursuit of systemic improvements that address barriers across all levels. By marrying high-quality laboratory practice with advocacy for accessible services, culturally safe care, and supportive policies, MLTs are poised to translate data into meaningful action, and from this multilevel perspective, the laboratory is not an endpoint but a facilitator of co-ordinated, patient-centred care. Embracing this perspective allows for the advancement of a practice that is compassionate, collaborative, and just, and it ensures that laboratory knowledge contributes to prevention, early diagnosis, effective management, and ultimately, to healthier communities.

Ultimately, determining where to intervene, whether in policy design or patient-level education, requires recognizing that meaningful change depends on the synchronization of all levels of the system.

References:

Accreditation Canada. (2023). Medical laboratory standards overview. https://accreditation.ca

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Browne, D. T., et al. (2024). Multilevel social determinants of individual and family well-being. BMC Public Health. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11002224/

Canadian Society for Medical Laboratory Science (CSMLS). (2023). The role of the MLT in Canadian health care. https://www.csmls.org

College of Medical Laboratory Technologists of Ontario (CMLTO). (2024). Quality assurance and professional standards. https://www.cmlto.com

De Benedictis, A., Lettieri, E., Masella, C., Gastaldi, L., & Macchini, G. (2019). WhatsApp in hospital? An empirical investigation of individual and organizational determinants to use. PLOS ONE, 14(1), e0209873. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209873

Diabetes Canada. (2024). Diabetes statistics in Canada. https://www.diabetes.ca

Evans, C. R., McFarland, M. J., & Umberson, D. J. (2018). A multilevel approach to modeling health inequalities at the intersection of multiple social identities. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.034

Government of Canada. (1985). Canada Health Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca

Huber, M., Knottnerus, J. A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A. R., Kromhout, D., … Smid, H. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ, 343, d4163. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163

McLeroy, K. R., Bibeau, D., Steckler, A., & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500401

Ontario. (2024). Preventing and living with diabetes. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/preventing-and-living-diabetes

Ontario Health. (2024). Improving access to diagnostic testing in rural Ontario. https://www.ontariohealth.ca

Ontario Ministry of Health. (2023). Published plans and annual reports 2023-24: Ministry of Health. Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/page/published-plans-and-annual-reports-2023-2024-ministry-health

Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). (2023). Social determinants of health and health inequalities. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/what-determines-health.html